Immersion in industries other than your own – for however short a time – can often reap benefits in understanding and knowledge that can then be applied back to your chosen field or specialism. But in the case of yacht and business jet interiors, some designers have seen sufficient synergies that they’re making a healthy living majoring in both disciplines, as this feature by Guy Bird from our 2010 archive explains.

So what is it that makes yacht and business jet interiors so similar? Of course both are forms of transport design involving moving people from A to B in restricted spaces, but both additionally specialise in moving very wealthy and influential people with exacting standards and expectations about getting from A to B in considerable comfort.

Given the speeds of such transport, both are also restricted by safety regulations affecting shape and materials. Spiky controls or sharp corners next to non-flame retardant upholstery would be rejected out of hand in either context.

Both usually feature bespoke designs and the owners of business jets often have a yacht too. As Rick Roseman of Texas-based RWR Designs – a significant player in both fields – puts it: “Large custom yachts are purchased by the same social and economic class of client as aircraft. Therefore a yacht designer will automatically have a grasp of the level of design and fit-out that these customers expect. Knowing and understanding the uniqueness of this particular ‘shared’ and very high-level market strata is hugely important.”

Designers of public transport might not have such an immediate empathy with their customers.

The design software used in both industries is often similar, recognised by engineering and suppliers alike, and includes AutoCAD, Alias Maya and Rhino. Budgets and timescales for these projects can even work out similarly too – although for very differently sized vehicles and different reasons. Roseman says interiors for a Boeing Business Jet or a US$50-60 million yacht could both come in at approximately US$18-20 million and take two years to complete. The per-square-foot price of the business jet is much higher due to the greater engineering work and materials needed, but on the other hand the yacht will need more design as they tend to be bigger floor spaces. Both can take the same amount of time due to the extra work needed to pass each industry’s relevant regulations.

Rules and regulations Indeed, the aviation industry has some of the most stringent regulations of any, such are the dangers of a part failing or a certain material catching fire thousands of feet up in the air. So much so that Rupert Mann of London-based Rainsford Mann Design (RMD) – which set up RMD Air specifically to service its growing number of yacht clients who also wanted private aircraft – feels the need to have the support of an STC (Supplemental Type Certificate) design consultant to provide all certified drawings for construction. By contrast, RMD would provide the equivalent full drawing packages for the yacht work it carries out by itself.

RWR’s Roseman believes reading up and fully understanding these regulations is the single most important aspect a yacht designer should remember when thinking about pitching for a business jet interior project. As he makes very clear: “The biggest pitfall facing a young designer who has accepted an aviation project, is proposing his/her concepts to the client – and then having to back-pedal because it simply isn’t deliverable as presented. This will automatically disappoint the client – not to mention quickly eroding his confidence in the designer. Knowing the ground rules is the best advice to adopt for any young designer.”

Understanding the subtle differences in the use of space in different kinds of transportation is also important. Adriana Monk, founder and design director of amDESIGN and a close design collaborator with high-end and ultra-modern yacht brand, Wally, explains: “In a car it’s about the driver plus maybe a few passengers, all sitting in their designated seats. In business jets you can move around a little more and all guests are treated equally. But it’s still a restricted vessel, and you need to consider all the activities that may take place, designing the space accordingly. In yachts you can cater to multiple guests who dispose of even more space and a greater choice of activities and entertainment. It’s almost like a hierarchy of luxury.”

Aside from greater potential for space and movement in yachts as compared to business jets, the reason for the mode of transport in question itself becomes fundamental. Business jets are by definition mostly about doing business as a mobile workplace, while yachts – although great places to impress a client or have a business lunch – tend to be more about pleasure.

A further design consideration follows from this general distinction. Business jet design – especially in the case of head-of-state or VIP aircraft – needs to take greater heed of security than yachts, especially in the design process, a factor that as Florida-based Patrick Knowles Designs concedes, makes conducting the design process – let alone talking about and publishing pictures of it – very sensitive.

Weight watchers

The final major contrast between the two relates to the fundamental difference in approach to transportation. Aviation designers have to consider the weight of parts and materials with much more care because not to do so would affect performance and running costs dramatically.

As RWR’s Roseman points out: “Weight is a huge issue in aircraft – each pound affects range and potentially maximum gross take-off weight. This doesn’t mean you can’t have the same look you might be going for in a yacht – but it definitely means how you get there will be different. It will require different materials, more stringent burn requirements and rigorous 16g certification requirements – not to mention considerably more engineering to support it all.”

The benefits of understanding such rigorous restrictions and material considerations can be significant when back designing yachts. According to Patrick Knowles, who started out in business jet and VIP aircraft, the positive design influences from aviation to marine are mainly technical. He cites two great examples. The first is a weight-saving design technique that allows yacht interiors to feature normally heavy marble and granite surfaces by water-jet cutting ultra-thin slices of those materials and bonding them to an aluminium substrate rather than using full-thickness stone – a process that can reduce weight by up to 75%. Also through business jet work, he discovered a high-density foam with excellent fire resistance called Divinycell that can be formed to house and protect delicate crystal and crockery in yacht cabinet drawers.

In terms of other influences, Knowles says LED lighting and huge plasma TVs got their first application within aircraft and are now filtering across to marine and indeed automotive and domestic interiors.

Aesthetic advantage

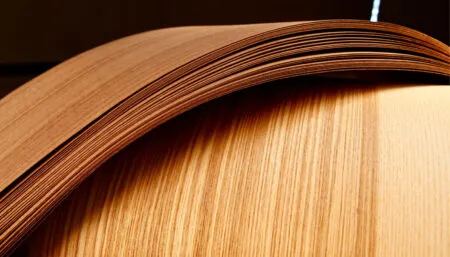

Regarding influence back the other way, Knowles believes the biggest factor is probably in the area of aesthetics. Rupert Mann of RMD agrees, believing the aviation industry to be a little behind the yacht world: “It’s my perception that the level of design for the aviation VIP industry is where the yacht interior industry was eight years ago – in other words the aviation industry is just catching on to the value of good design and aesthetic. The creative explosion is taking longer in the VIP industry because these assets are business tools first and leisure assets second. In addition, the regulations have been such that material choice has been restrictive. Now though, with the advent of improved technology, designers have more scope with the material finishes and aesthetic – digital veneers being a good example.”

Mann also senses that business jet customers’ tastes are changing, as he continues: “We must also recognise that owners are getting more ambitious with how they want their aircraft to reflect their lifestyle and are requiring designers to push the boundaries more.”

Multiple choice

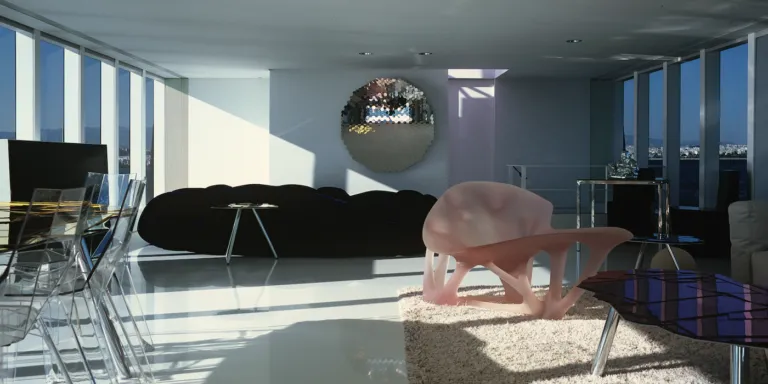

Designers with more diverse backgrounds will certainly help. Ivana Porfiri of Milan-based Porfiri Studio is pushing modern design through influences well beyond aviation, as she concedes: “I am absolutely not a specialist. My experience is in many fields, in yacht design, as well as in product design, in housing and working spaces. I think multi-design experiences are always better as they make for a more rich vocabulary and allow the circulation of ideas and innovation.” Her recent yacht project ‘Guilty’ is a good example of such a challenging approach.

Ultimately, though, design progression and business success in aviation has to come in tandem with pleasing the customer. And as pointed out earlier, given that many yacht and aviation customers are the same people, those that get it right will benefit twice over, as RWR’s Roseman concludes: “If you can make him or her ecstatic over the results, which ideally means giving them more than they expected, you will be doing more work for them – be it yacht, aircraft or home. This is a ‘theorem’ that is absolute.”